What do chargebacks mean for your business?

To understand how chargebacks work (and how they don’t), it helps to have a basic understanding on the rationale behind them, and the impact they have on everyone involved.

What is a chargeback?

In the most basic terms, it’s the reversal of a credit card payment.

If you’re a merchant (e.g. a hotel), chargebacks can result in lost revenue, laborious efforts, and be a frustrating threat to your business. If you’re a consumer, chargebacks represent a shield between you and dishonest merchants. If those two things seem at odds, well, that was never the way it was intended.

The Purpose of Chargebacks

While chargebacks can appear very similar to traditional refunds, there is one key difference: rather than contact the business for a refund, the consumer is asking their issuing bank to forcibly take money from the merchant. This could be because the customer does not believe they received what they paid for; or more commonly, does not recognise the charge on their statement. An investigation is then made by the customer’s bank and card networks, and if the bank and card networks decide that the cardholder’s request is valid, funds are removed from the merchant’s account and returned to the consumer.

Chargebacks are designed to keep customers safe. The risk of a forced reversal of funds ensures merchants do their best to deliver the product or service that was advertised.

Chargebacks help protect cardholders from the effects of merchant fraud. Giving a cardholder the ability to file a chargeback on a fraudulent credit card transaction negates the customer’s risk and provides them with confidence to use their card for a multitude of purchases.

The History of Chargebacks

When credit cards were first introduced In the early 1970s, the banks had trouble convincing the public of the safety of using their new product. Getting mass adoption for credit cards was hard because people were worried that if the card was lost or stolen, a criminal could then use it for unauthorized transactions. The cardholder in this case would be liable for paying for these fraudulent transactions.

Another issue that started to arise was fraudulent merchants using the card information received during payment to add additional charges. In 1974 The Fair Credit Billing Act of 1974 was created to address this by creating what is called a chargeback.

By requesting a chargeback, the cardholder could now go around the merchant and secure a refund from the bank itself. The bank, in turn, could void a credit card transaction, then withdraw funds that were previously deposited into the merchant’s bank account and charge the merchant a hefty fee. With these new trust features, credit card use exploded and banks finally saw the adoption they were hoping for.

When Can a Consumer Issue a Chargeback?

Basically, a cardholder can request a chargeback from their bank for any charge on their card. This does not mean that their request will be successful, and there are certain things that a cardholder should do before taking this action.

The first thing a customer should always do, except in the case of a lost or stolen card, is contacting the merchant directly.

The goal is to resolve the issue without the banks getting involved. Most of the time, there is a simple communication issue that can be sorted out within 5 minutes. This could be due to an honest mistake on the part of the merchant, who will issue a refund, or most commonly because the cardholder does not recognize the name of the merchant on their statement. This is extremely common among merchants who are part of a larger corporate holding company.

If the merchant won’t work toward a solution, a chargeback could be the only option. However, this should be a last resort, as it can be very harmful to the merchant if falsely issued.

The reason is that with a chargeback, the cardholder keeps the purchased product or service and gets the cost of the item refunded. So the merchant basically gives the customer the product or service for free and has to pay a chargeback penalty. In the case that the merchant is honest but can not prove it, the customer has literally stolen from the merchant.

The Effects of Chargebacks for Merchants

Chargeback Fees: Each time a consumer files a chargeback that is deemed to be successful, the merchant is hit with a fee ($20 – $100 per transaction). Even if the consumer later cancels the chargeback (for example, if it was filed because of non-delivery, but the item shows up a few days later), the merchant will still have to pay fees and administrative costs associated with the process.

If the merchant incurs excessive chargeback fees within a certain time period, they can also receive extreme fines ($10k+) which can cripple a small business.

Lost Merchandise: In the event of a successful chargeback, the customer does not have to return the product. This causes loss of inventory, which leads to not only lost revenue but can disrupt operating flow for valid future customers.

Placed on High Risk: If the merchant’s chargeback rates go above a certain threshold, their payment provider could place the merchant into a high-risk category. This causes the merchant to pay larger transaction fees and eats into their margins.

Termination of Account: In extreme cases, the payment provider could terminate the merchant account. A merchant might then be placed on a blacklist viewable by other payment providers and would no longer be able to accept card payments, in many circumstances bankrupting a business.

Time, Stress, and Labour: Even if the business is in great financial condition and can weather the hits from the fees incurred, each chargeback that is issued takes up valuable resources for the business in the form of account reconciliation, labour efforts needed to provide the requested documentation, and the mental capacity that could be used to grow the business.

The Effects of Chargebacks for Consumers

The consumer also has some accountability for requesting chargebacks. In order to maintain a system where consumers can’t go wild and request a chargeback for every transaction, valid or not, consumers can suffer the following:

-

If a merchant successfully disputes an illegitimate chargeback request, the consumer might have to pay the accompanying chargeback fees.

-

If a consumer files a chargeback and that the bank classifieds it as fraudulent, the credit card account can be closed. This will result in a lower credit score for the consumer.

-

Filing a successful chargeback means the cardholder won’t get a refund for several months. Meaning they still have to pay for the initial transaction in time.

-

Banks will mark cardholders who “cry wolf” too often and they won’t get the help needed in cases of legitimate fraud.

-

Finally, merchants raise their prices to compensate for predictable chargeback fraud.

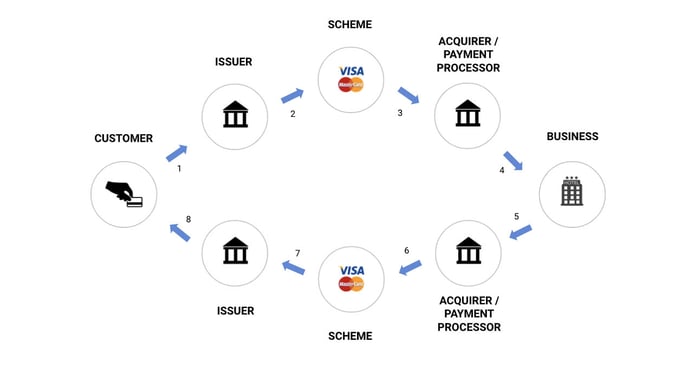

The Chargeback Flow

There are lots of players and moving parts involved in a chargeback. This diagram shows a typical end-to-end process:

-

The cardholder contacts their issuing bank and asks for a refund.

-

The card issuer returns the transaction to the merchant bank through the respective scheme network (Visa or MasterCard).

-

The scheme network reviews the validity of the transaction to be charged back and, if appropriate, forwards it to the merchant’s payment provider.

-

The merchant’s payment provider receives the chargeback and either resolves the issue or, if unable to do so, forwards it to the merchant.

-

The merchant receives the chargeback. If the merchant has proof that the transaction is valid (e.g. a sales receipt), the proof is submitted (re-presented) to the merchant bank. If the merchant is unable to produce a proof, the chargeback may have to be accepted.

-

The merchant bank receives the represented transaction and sends it on to the credit card company or association.

-

The credit card company or association receives the represented transaction and, if appropriate, forwards it to the card issuer.

-

The card issuer receives the re-presented transaction and, if appropriate, re-posts it to the cardholder’s account. If the chargeback issue is not adequately addressed, the card issuer may submit a dispute with the credit card company or association.

-

The chargeback process ends with the cardholder receiving information resolving his or her dispute. If the merchant’s evidence is compelling enough to refute the cardholder’s claim, the transaction will be posted to the cardholder’s account a second time. The funds that were originally deposited into the merchant’s account–then removed through the chargeback–will be deposited once again.

Steps to Take to Mitigate Chargebacks

As you can see, chargebacks can cause a lot of harm and damage to a merchant. Fortunately, there are a number of ways a business can reduce the impact chargebacks have on them.

Proper Transaction Statement Labeling: One of the largest causes for a chargeback request is due to the cardholder not recognizing the name of the merchant on their statement. Many times the charge will come through as the corporate holding company. Many payment processing companies, like Hotel Link Pay, ensure that the local merchant’s name appears in order to address this.

3D Secure: Another feature that is available is called 3D Secure, or 3DS. This works as a 2-factor authentication for a cardholder, so after a transaction, the customer receives a text message or email requesting a confirmation of the purchase. This gives the issuing bank some extra proof that the customer was indeed the one who made the purchase and drastically reduces fraudulent charges.

Looking for more information on chargebacks? Contact us.